Tagged: Georgia

November 12th-14th – Hitch-hiking from Tbilisi to Istanbul

Goga picked us up on the highway just outside Tbilisi, round the first corner we passed an ancient looking church and he crossed himself before putting his foot down on the accelerator. Had I have known then the speed he was about to drive at there is no doubt I would also have crossed myself and added in three “Hail Mary’s” and an “Our Father” too…

Goga’s day job was as a financial manager for Georgian railways, but somewhere inside him was the soul of Ayrton Senna struggling to get out. He turned the roads of rural Georgia into his personal formula one track as he drove to the funeral of a friend’s father as if his life depended on it.

Still having rushed from summer into winter in the space of one week in Turkey it was nice to be going back one season here. Yesterday in Tbilisi I’d read a quote from George Eliot saying that if she was a bird she would just pursue autumn, the loveliest of the seasons, around the world. And here in the Georgian valleys, as far as I could see through my fingers, was a perfect autumn day on which she would have loved to have alighted, from the carpet of red leaves on the floor to the plump orange persimmons brightening up otherwise entirely bare trees. I have been frequently amused by the sight of the persimmon ever since it was recently described to me by a retired English-Texan lady with immaculate elocution as “the most erotic of fruits.”

After Goga dropped us off the next ride was a Turkish truck driven by Jesus (actually Issa which is the Muslim version of the same name). In his truck we got our first sight of the Black Sea, the moody cousin of the Mediterranean (which the Turks know as the White Sea). I can imagine the clouds that the Mediterranean gives birth to to be the fluffy, flighty ones that breeze around carefree, whereas the Black Sea’s progeny would be the grump, heavy-set ones that do the hard-work of pouring rain all over the earth. We approached the Black Sea border at dusk along roads so rough that we were shaken about in the truck’s cabin as if we were all dancing energetically to the northern Turkish folk music on the stereo.

A Georgian guy took us to the border and arranged to meet us on the other side to drive us on into Turkey but unfortunately we didn’t make it. One of my general themes is that Turkey, in direct contrast to its popular image amongst some in the west, is filled with the most generous, gracious, and gentle people you could ever hope to meet. But, as I discovered at this border crossing, it also has a very effective screening and selection programme for its bureaucrats to make sure that no-one with any of those qualities is given a governmental job.

The border staff couldn’t understand that our visa allowed multiple visits up to a total of 90 days in every 180 day period and refused us re-entry to Turkey, leaving us stranded in Georgia. Catherine’s attempts to explain the actual visa regulations to the commanding officer were just met with repeated shouts of “exit, madam!” When she asked for his name he refused to give it, making me think “who the fuck are you, Rumpelstiltskin?”

Anyway fortunately the border staff’s ignorance of their own country’s border laws meant that they also didn’t know that you can’t get two visas in one 180 day period so they agreed to issue us a new one. It was annoying paying again as we already had a valid visa, but it was better than the alternative of being trapped in Georgia and needing to pay for expensive flights out in order to complete our final few months travel plans.

Ultimately for us the episode, while a bit stressful, was just a minor irritant. I feel, however, for the Turkish people who must have to put up with ignorant and willfully deaf authorities on a daily basis.

Our main lift the next day, along the beautiful Black Sea coastal road, was from a Kurdish truck driver named Ramazan, who initially said he going to Ankara. He was very hospitable, buying us lentil soup at a truck stop and providing us with numerous Turkish coffees on the go from the mini kettle he kept in his cabin. Actually Catherine was pouring the coffee, I was staring it through and then I noticed that Ramazan, oblivious to the road and traffic flying around us, had taken on the role of over-seeing the whole process. Deciding that, as we were speeding along in a ten tonne truck, at least one of us should look at the road I decided to opt out of my staring duties.

Ramazan dropped us in a dark town that had evidently never seen a tourist before, but which was very excited about its chickpeas which it advertised in every shop along the highway in the sort of huge neon signs normally found on casinos or dodgy nightclubs. Two friendly locals drove us to a cheap hotel which appeared to be a students’ hall of residence – we got a suite there for 30TL (£10) including breakfast.

On the third and final day we hitched successfully to Istanbul, via Ankara (Turkey’s capital). The most interesting lift of the day, and possibly of our whole hitch-hiking career, was with Gorkem a young Armenian. Gorkem was a member of Carsi, the Besiktas football fan group who are famous for campaigning for left-wing causes. Most of the groups leading members have been arrested after figuring very prominently in the recent anti-government protests in Istanbul.

Gorkem’s day-job, away from Carsi, was even more interesting. He worked as a war photographer and has been to both Iraq and Afghanistan. On one assignment in the latter country he was shot twice. Gorkem was now focusing on his own photography projects, making regular trips into civil-war torn Syria to photograph the persecuted Kurdish people there as a means of telling their story to the world. After all our recent experiences in Kurdish Turkey and Iraq, meeting Gorkem made this a very fitting final hitch of our journey to Istanbul.

Finally we reached the old Ottoman capital and crashed into the wall of defensive traffic which has been erected around the modern city. If only the Byzantine Empire had thought of doing the same thing back in 1453 the invading Turks would probably have got bored and gone away. Still, despite the grindingly slow traffic surrounding it there is always something exciting about arriving in Europe’s largest city. Here we were within ten minutes of the Bospherous Bridge crossing that was going to finally take us out of Asia, where we have spent the vast majority of our last five and a half years travelling. Thanks to traffic the actual crossing took closer to an hour, but it was worth the wait – there was the Topkapi Palace, Aya Sofia, the Blue Mosque and all lit up in lights and waiting to welcome us to the start of the European leg of our journey home…

Facts and figures from the hitch from Tbilisi to Istanbul

Total distance travelled – 1,858 km

Number of lifts – 19

% of the drivers who smoked – 100%

Origins of the drivers – 2 Georgians, 3 Kurds, 2 Laks, 10 Turks, 1 Armenian, 1 Syrian

Occupations of the drivers (were known) – financial manager, truck driver (x4), wrestler, road construction company manager, coal salesman, war photographer

Hospitality offered – free accommodation for the night (twice), 4 bowls of lentil soup, 2 salads, 2 baskets of bread, 8 glasses of tea, 4 Turkish coffees, 38 cigarettes (i.e. one each offered on every lift), a bag of hazelnuts, one pomegranate and 10 tangerines

November 11th – Falling in Love with Georgia

Today I learned that drinking beer in Tbilisi city centre is cheaper than drinking tea. Whilst in the afternoon in a cellar bar on the main drag, Rustaveli Avenue, we bought a litre of local white wine for two quid. And between the top and the bottom of that jug I fell in love with Georgia.

It wasn’t just the cheap wine that did it, of course. It was also a wander round the romantically dilapidated streets of the quiet old town, and also the taste of a pot of lobiani on an autumn day, and also a visit to the coolest café we’ve ever seen, and also the fact that in the bar they played Nick Drake and Leonard Cohen. All of these wonderful things combined to make me fall in love with Georgia….but mostly it was the cheap wine.

In the old town I went looking, without success, for a Georgian knight’s costume for my nephew. But what I did find there was amazing. Beautiful streets full of elegantly houses covered in crumbling plaster and seemingly held together by rickety, rotting outside staircases. On the first floor crumbling balconies clung on to their hosts for dear life, trying to avoid collapsing onto the people below. Coming from Liverpool I’ve got a natural love of beautiful old buildings falling into disrepair.

In one street we found the Linville Café. Access was up a flight of stairs and entering the florally wallpapered space inside was like visiting your nan’s house, if your nan was an eccentric Georgian artist with upside down lamps hanging from her ceiling and Belle and Sebastian on the stereo. The song was one I hadn’t heard before, “My Wandering Days Are Over” and mine nearly are, and if Liverpool was as cool as Tbilisi, and the wine was as cheap, they probably would be for ever…

November 10th – the Anatomy of Georgian Melancholy

One day in 1993 a young refugee from Abkhazia arrived in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital, with next to nothing to his name. Starting life again from zero he decided to try to get on by teaching himself English from a copy of Richard Burton’s 17th century classic “The Anatomy of Melancholy” which he’d bought from a stall and a Russian-English dictionary which he’d found on the street.

“The Anatomy of Melancholy” is an unusual book which analyses the causes of misery, finding explanations ranging from the activities of ghosts, evil spirits and witches to others which this young refugee would have recognised such as war, displacement and fear of the future.

I cannot imagine how cool your English would end up sounding if you had learnt the language from such a source, but I only hope that the young refugee, the artist Lado Pochkhua, is still speaking like this in his new home New York. Perhaps he would sound something like a shopkeeper I met in India who memorably told me when I was asking for directions in Jaipur “look to yonder roundabout where the buses are going hither and thither.”

Lado Pochkhua’s photographs from his refugee days were being exhibited in Georgia’s National Gallery under the title “the Anatomy of Georgian Melancholy.” And it was a fascinating and fantastic collection, stark black and white portraits of fellow refugees, pictures of boys playing football in the snow and simple images which contrasted a refugee’s dream of escape to elsewhere with the everyday details of life trapped where they were – the trail left by a plane in the sky above the bare branches and twigs of winter trees.

But even more interesting than the pictures, for me, was the artist’s commentary. Writing about a shot of peasant refugees sat around a picnic table he discussed the effect that losing their land has on people. For him the loss left the peasantry utterly bereft, as the rhythm of their days and years was utterly dependent on working the land and without it they were left without any sense of time or any hope for the future.

We’ve spent lots of time on our travels with people in tropical countries who, although cash poor, are land rich, and it is my belief that anything which takes that land away from these traditional owners, such as the activities of rapacious governments and robber barons CEOs, is one of the great evils of our time.

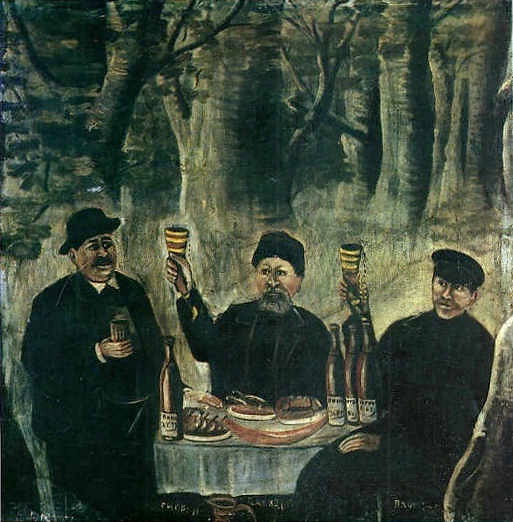

Away from the photography the collection of paintings focused mainly on the early 20th century works of two Georgian masters, Nikos Pirosmani and Lado Gudiashvili. Though different in approach, Pirosmani’s naive simplicity contrasting with Gudiashvili’s more sophisticated and sensual style, the two artists produced lots of similar, typically Georgian, scenes. Paintings of drinking and feasting featured prominently with rows of surprisingly stern faced, black-clad men sitting at tables in fields with mountains of food in front of them. Elaborate toasts are a touchstone of Georgian culture and the men invariably held half-raised horns of wine in their hands.

Even with such subjects that should have been jolly, I couldn’t help but notice the darkness of all the paintings, not just in the clothes being worn by the feasters but also in the surrounding landscape, and especially the skies which were invariably black-blue or pure black. It seems that there is a strain of melancholy running through all of Georgian culture, even amongst those people not affected by war and landlessness – so I guess it must be down to the ghosts and witches.

As we had arranged two couchsurfs in Tbilisi, yesterday we left the place of our first host Zura to move to that of our second, Scott a Canadian geologist. Zura had first introduced us to Georgian cooking with a plate of the national dish, khinkali, a kind of dumpling which in Himalayan India and Nepal would be called a momo. The unusual cuisine of Georgia is apparently one of its tourist attractions, and Scott expanded our experience of it with such dishes as aubergine with walnut sauce and pomegranate and lobiani, a bean dish reminiscent of an Indian urid dal. Georgian food does seem a unique mix, but I haven’t yet seen anything here to equal the oddity of Turkey’s “chicken breast pudding.”

Over dinner Scott produced his party piece, a fragment of rock from Greenland, which, at around 4 billion years old is one of the most ancient on the earth. Somewhat struggling to top that we produced a fragment of flintstone from Göbekli Tepe which we had been told was 8,000 years old but, understandably, Scott didn’t seem very impressed.

As well as his geological work Scott is also translating a series of satirical Russian children’s stories by an author from Archangel, where he lived pre-Tbilisi. While discussing the translation I learnt an interesting Russian idiom, “an American smile”, which means an insincere one. Russians apparently are very scathing of people who smile when they don’t mean it, and they reserve their own smiles for when they are genuinely delighted.

Georgia may have its melancholy but after a great day and with a bellyful of beer I went to bed grinning like a Russian.

November 9th – Georgia on My Mind

In Tbilisi today everybody was getting married. The grey sky and drizzle did not dampen the enthusiasm of the wedding parties that were driving round every street, beeping their horns so incessantly that, if I closed my eyes, I could imagine I was back in India. By the waterfall which flows through the historic centre of the town, brides in white dresses and grooms in traditional Georgian costume, basically a dress with a waistcoat and a sword, were posing for photographs. And every church was full to the brim with friends and families queuing to give their best wishes to newly-weds, all watched over by the wide-eyed icons of the Georgian orthodox church on the surrounding walls.

Taking a drag from his cigarette, our couchsurf host Zura looked down from the street onto another church emptying out its pious crowd. Commenting not on the wedding but on the faith itself, he said ‘some people think it’s nice, but to me they are idiots. Racists and homophobes, their thinking is all wrong.’ Later I would hear that a recent violent attack on a gay pride march in central Tbilisi had been led by a group of orthodox priests. Obviously they missed that little bit in the Bible about those without sin casting the first stone…

Zura was the perfect host to provide an introduction to Georgia, a free-thinking, libertarian with an amused, and often exasperated, sense of his country’s culture, past and present. Certainly Georgia is a country worth getting to know. A European style-Christian outpost stuck in the mountains in between Russia and the Muslim countries of central Asia and the Middle East. Georgia is so different from all the rest of the world that its language is unrelated to any others except for a mysterious connection with Basque.

Georgians, as portrayed by Zura, are a people full of hospitable spirit and hot-blood, both apparently common qualities amongst those whose homeland is the highlands. Their culture revolves around wine, elaborate toasts, feasting and fighting. The two or three fights Zura sees on the streets on every night out could be the modern version of the old highland Georgian tradition of duelling.

More seriously, according to Zura, 80% of what we would consider the Russian mafia are Georgian. Certainly the biggest criminal of the Soviet Union, Josef Dzhugashvili, was Georgian. And if you’ve never heard of him it’s only because he’s much better known by the name he gave himself, the “man of steel”, Stalin. Most modern Georgians apparently see Stalin as a criminal, but the vestiges of pride in him amongst some sections of society can be seen in the memorabilia for sale in the shops – the perfect presents for any hard-core communist history deniers in your life, from Stalin tea mugs to Stalin wine.

Zura was born in the same year as me, so spent the first 13 years of his life living in the Soviet Union. ‘A typically quiet Soviet childhood’ came to an end with the collapse of the empire and the creation of an independent Georgia. Crime spiralled out of control and Zura witnessed a sniper on top of the old building where he still lives shooting a man dead and then dragging the corpse down the stairs, the bloody head banging on each of the steps.

Modern Tbilisi, however, as far as I could tell, is a pretty peaceful place. The only violence I saw on the streets was a golden man pausing halfway through pushing a spear through the mouth of a dragon, the eponymous St George up on a pedestal in Freedom Square (formerly Lenin Square).

We climbed up through the backstreets with Zura to a ruined castle over-looking the city. Standing on the walls I enjoyed watching the drizzle in the lights of the castle walls. Drizzle is a phenomenon that doesn’t exist in most of the countries where we’ve spent the last five years. I like the way it doesn’t so much fall like regular rain but dances in the sky like the lightest of snow.

Tbilisi at dusk looked an attractive place. Behind us the fairy lights on a mini-Eifel tower overlooking the old town sputtered in the fading light and mist obscured the top. With no high-rise visible in the city centre the buildings that stood out where the illuminated churches, I could hear the strains of “Amazing Grace” (written, incidentally, by a Liverpool based ex-slave trader) rising up from one of them. Elsewhere I could see a still functioning synagogue, a testimony, according to Zura, to the lack of anti-semitism in Georgia’s history.

One old neo-classical building with a glass dome on top reminded me of Berlin’s Bundestag (Parliament). The German version seems to me an excellent representation in brick and glass of the way democracy is meant to, as the public can climb up above their politicians to look down on them. In the Georgian version, however, no member of the public is allowed into the glass dome.

Zura looked down on all the signs of Tbilisi’s history in the city centre and criticised the Georgian people. ‘They always say “we were the greatest in the 10th century”, I couldn’t give a shit about that, I only care about what we are now, and what sort of country my daughter will grow up in.’ For Zura the current government are ‘idiots’ and the previous government were ‘idiots, just not as big idiots as the current government’. Georgia, in his mind, suffered from too many people who were “not adequate”, meaning they were lost in the country’s glorious medieval past, trying to artificially keep alive cultural elements which were naturally dying out, and failing to recognise the economic solutions needed to improve the country in the modern world.

Today in Tbilisi everybody was getting married. What sort of country the children of all the weddings will grow up into is anybody’s guess.

8th November – Leaving on that Midnight Hitch to Georgia

In today’s blog I visit an ancient Armenian vision of the world after humanity’s extinction, and I also explain how Catherine and I came to arrive in Tbilisi, Georgia at 4am, penniless, mapless and clueless, in an Iranian truck blaring “Gangnam Style”.

First thing in the morning I took a lift out from Kars to Ani, Armenia’s medieval capital and once a silk-road city of great importance with a population to rival Constantinople. The journey out there, through a desolate slab of bitterly cold central Asian style steppe, gave no suggestion that we were approaching an ancient capital. The houses of the few villages strung out along the roadside where built of stone and topped with earth and grass, a sensible way of insulating against the winter whilst not risking a crushing weight falling on the houses’ inhabitants when one of this region’s frequent earthquakes strikes.

The road ended in Ani. Dramatically located overlooking an earthquake-created gorge that marks the border between Turkey and Armenia, the ancient city of Ani is so deserted that it felt as if we’d come to the ends of, not just the country, but the earth. The only sound was the flowing water deep in the gorge below and occasional distant birdsong.

Ani was built in this dramatic location to prevent invaders from outside, but the real danger to its long-term survival was the enemy within, or rather beneath. Numerous invaders passed through including Seljuk Turks and Mongols, but the city’s final destruction was the result of it being located right on top of an enormous fault-line. The surviving buildings, churches, mosques, old silk road caravanserais and palaces, have all been dissected by earthquakes. The crumbled walls made me think of those children’s history books where the illustrations present a medieval castle or a roman baths with the exterior half removed so you can see the life inside.

But in Ani there is, of course, no life left. The city was once home to 100,000 people but today there were only four tourists and a few goats. In addition a few saints with faded haloes still stood on church walls waiting for judgement day. Neither Christian nor Islamic buildings have been spared destruction by the forces underneath the earth. Neither the swastika on the city walls (an ancient sun symbol of the Turks and many other Asian cultures), nor the crosses or crescents on the church and mosque walls have prevented the city’s destruction.

Ani in its bleak beauty, and with signs of past-life everywhere contrasting with its utter emptiness today, is a vision of what the world will look like when humans no longer exist. It made me think back to a recent visit to Dubai, where huge edifices are now being erected in a city as successful in the modern world as Ani was in its day. One day some future tourist will visit Dubai and marvel at the grandeur that must have existed there before it was abandoned. And one day there won’t even be a tourist left to see the ruins at all.

But my morbid musings in Ani were lightened somewhat by another member of our party, a middle aged Japanese woman who became obsessed with photographing me everywhere around the site. As she was alone I offered to take her photo with her camera, but she would always say “no, photo of you”. At every ruined building she would shout “Mr Hitch-hiker! Mr Hitch-hiker!” and she took so many snaps of me, including ones when I was just walking along not suspecting I was being snapped, that her film ran out.

On the way back from Ani to Kars the driver told us that Turkey did not build its first car factory until 1970, and that up until that date everyone rode around on horseback. Fortunately there are cars, and trucks, in and around Kars today so Catherine and I were able to complete our plan of hitch-hiking on to Georgia in the afternoon. As the trucks were slow on the windy mountain roads we only reached the Turkish town 15km from the border in the early arriving dark (4:30pm). We hitched to the border with an Iranian truck driver scrunched up on the front seat of a vehicle so old that it might have been the first one produced by that factory back in 1970.

Every turn of the wheel required an enormous wrenching on the part of the elderly driver, and produced a groan from the reluctant engine. Despite the difficulties of steering the beast the driver was not deterred from holding a cigarette in one hand and constantly changing the CD in the player above his head with the other. No song would be given more than 5 seconds before he decided to swap the CD, which meant he wasn’t looking at the dark mountain road ahead. Eventually some Iranian boy band dance pop came on and I decided to feign enthusiasm with big thumbs up and shouts of “good, good!” and even a bit of head-nodding, in the hope of getting him to leave the track on so he could focus on driving. Although less than a minute into the song I was regretting my decision and would have preferred to take my chances with crashing.

Gettng stamped out of Turkey was no problem but walking across the border into Georgia proved difficult. We were detained by the border police for nearly an hour and subject to a bizarre very occasional interrogation, where they would come over and ask us a random question such as “are you married?” then disappear for twenty minutes before returning to ask us our brothers and sisters names. Obviously our siblings aren’t on any lists of Georgia’s most wanted cos we were eventually allowed in. But as it was so late and dark finding a truck going on to Tbilisi was a struggle.

We stood in the freezing cold just across the border watching as every truck crossing parked up to sleep for the night. Eventually we were approached by another Iranian with a Georgian friend in tow to translate. He was driving to Tbilisi and offered to take us, while the Georgian offered a shot of vodka to warm us up.

We were so grateful for the lift but the truck was slow and stopped frequently and inexplicably. The journey to Tbilisi took over four hours, during which time I mostly slept, although I was periodically awakened by the song Gangnam Style which the driver had great enthusiasm for. Every time it came on his CD player he would turn it up to near maximum volume and wake me up, before turning the volume back to normal levels for the next tune.

The arrival in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital, at 4am was marked by a final blast of “Gangnam Style” and the truck driver nearly ploughing straight through a heroic looking horseback statue of “King David the Builder”, the regal Georgian equivalent of our own Bob. We left the truck with great gratitude but also realising we had no idea where we were within Tbilisi, no idea of how to get to the home of our couchsurf host (whose phone number we had lost en route), no Georgian currency in our pockets, and no idea which one of us had wanted to come to Georgia in the first place.

Still we sorted it out, with a vague memory of the street name we needed to reach we found a taxi driver who would take the few US dollars we had to get us there. Then we found a hostel with wi-fi and were able to dig out our host’s number, and then we were delighted to discover that despite it being past 4am he wasn’t sleeping, in fact he’d just returned from his night out. We ended up sitting up chatting till past 6am and learned a lot of amazing stuff about Georgian culture – but that will have to wait for another blog cos this one, like the day it describes, has gone on for far too long and now it’s time for bed.